وقعت أحداث الاضطهاد ضد السكان الصرب في كوسوفو العثمانية في عام 1878، نتيجة للحرب الصربية العثمانية (1876-1878). اللاجئون الألبان القادمون إلى كوسوفو والذين طردهم الجيش الصربي من سنجق نيش في هجمات انتقامية وعدائية للسكان الصرب المحليين.[1][2][3] شاركت القوات الألبانية العثمانية أيضًا في الهجمات، بناءً على طلب السلطان العثماني عبد الحميد الثاني.[4]

الخلفية

- مقالة مفصلة: ترحيل الألبان 1877-1878

خلال الحرب الصربية العثمانية في الفترة 1876-78، تم طرد ما بين 30,000 و70،000 مسلم، معظمهم من الألبان، من قبل الجيش الصربي من سنجق نيش وهربوا إلى ولاية كوسوفو.[5][6][7][8][9][10] في سياق الحرب الصربية العثمانية، أطلق السلطان العثماني عبد الحميد الثاني قواته المساعدة، المؤلفة من ألبان كوسوفو، على الصرب الباقين قبل وبعد تراجع الجيش العثماني في عام 1878.[11] نشأت التوترات في شكل هجمات انتقامية من قبل اللاجئون الألبان القادمون على صرب كوسوفو المحليين الذين ساهموا في بداية الصراع الصربي الألباني المستمر خلال العقود المقبلة.[12][13]

1878

18-19 يناير

مع الاستيلاء الصربي على نيش، انتظر قرويو كومانوفو الجيش الصربي الذي ذهب إلى فراني وكوسوفو.[14] سُمعت نيران المدفعية الصربية طوال شتاء 1877/78. لقد فرت القوات الألبانية العثمانية من ديبار وتيتوفو من الجبهة وعبرت بينيا، ونهبت واغتصبت على طول الطريق.[14]

في 18 يناير 1878، نزل 17 من الألبان المسلحين من الجبال إلى أوسلاري، وهم يهتفون خلال دخولهم القرية.[14] وصلوا أولًا إلى منزل آرسا ستويكوفيتش، الذي نهبوه وأفرغوه أمام عينيه، مما أغضب ستويكوفيتش الذي شرع في ضرب أحدهم. لقد أصيب برصاصة في بطنه وسقط، ومع أنه ظل حيًا، لكنه تعرض لصدمة ووجه ضربة قوية إلى رأس مطلق النار، ومات معه. ثم دخل القرويون بسرعة في معركة مسلحة مع الألبان وقتلوهم.[14]

في 19 يناير 1878، اقتحم 40 فارًا ألبانيًا منسحبًا من الجيش العثماني بيت المسن تاشكو، وهو قن، في منطقة بويانفيتش، حيث قيدوا الذكور واغتصبوا ابنتيه وقريباته،[15] ثم شرعوا في نهب المنزل وغادروا القرية.[14] قام تاشكو بتسليح نفسه وإقناع القرية بالانتقام، وتعقبهم في الثلج وتضاعفت أعدادهم.[16] تم تشتيت الهاربين الألبان، وهم في حالة سكر، وتم اعتراضهم أولاً في لوكارسي، حيث تعرض ستة منهم للضرب حتى الموت.[16] لقد قتلوا جميعهم.[15]

مع طعم الدم والانتقام والنصر، نما الانتقام إلى انتفاضة، حيث أصبح المتمردون ثوارًا، وركبوا وهم مسلحين على الأحصنة كجنود عبر قريتي كومانوفو وكريفا بالانكا ودعوا إلى التمرد.[14] تم تعزيز الحركة من قِبل ملادين بيلجينسكي ومجموعته بقتل حراميباشي العثماني الألباني برام شتراوي وأصدقائه السبعة الذين جُلبت رؤوسهم المقطوعة كجوائز واستخدمت كأعلام في القرى. في 20 يناير 1878، تم اختيار قادة انتفاضة كومانوفو.[16]

26 يناير

| ||

|---|---|---|

| المكان | Panađurište hamlet, بريشتينا, الدولة العثمانية (now كوسوفو) | |

| التاريخ | January 26–27, 1878 | |

| السبب | Advance of the Serbian Army | |

| المشاركين | ألبان | |

| الوفيات | Numerous صرب murdered, as well as Albanian attackers | |

| الخسائر المادية | Houses set on fire | |

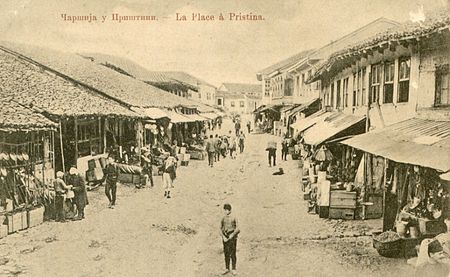

وفي الوقت نفسه، وقعت مذبحة من الصرب في بريشتينا على يد ألبان مسلحين استغلوا الفوضى والارتباك الذي تبع ذلك.[14] وفي 26 يناير، جاء اللاجئون من القرى التي يسكنها الألبان إلى بريشتينا وأخبروها أن المواقع الأمامية الصربية موجودة بالفعل في غراتشانيكا. بدأ الألبان يهاجمون المنازل الصربية، وسرقوا وخطفوا وضربوا وقتلوا.[17]

تجمع الألبان المسلحون في المحلة التي يسكنها الصرب في باناجوريشت،[18] حيث وقعت معظم الفظائع.[19][20] طرق خمسة رجال باب صانع الأسلحة جوفان جانيتشيفيتش (المعروف باسم جوفان تشاكوفاتش).[17] لقد كان يوفان صديقًا للمعلم الصربي كوفاشيفيتش في بريشتينا.[19] ونظرًا لعدم فتح أي شخص، ومن أجل عبور الجدار، وقف الثلاثة على بعضهم البعض.[14] أطلق جوفان النار على الشخص الذي كان ينظر إلى الفناء، فتعرض المنزل لوابل من الرصاص، وقُتلت زوجة يوفان. أخذ يوفان أطفاله وكسر الجدار إلى منزل جاره، وهو صديق تركي، ودفعهم عبر الحائط. ورد قريبه ستويان، ووقف هجومهم. دافع يوفان وستويان عن نفسيهما، بينما مر نصف يوم بالهجمات والضحايا. غادر المهاجمون المبنى عبر شارع irietiri Lule، ثم عادوا بالتبن والقش وأشعلوا النار في المنزل الذي كان ممتلئًا بالدخان. استسلم ستويان على وعد من besa، ومع ذلك فقد قطعوا رأسه الذي رموه في الشارع. دخل يوفان، الناجي الوحيد، الطابق السفلي عندما انهار المنزل. ومع جرح في الكتف فقد هرع خارج الميدان وتمكن من إطلاق النار على ثلاثة من المهاجمين، قبل أن يُقتل. لقد ساروا في سوق بريشتينا ورأسه على عمود.[14]

من أجل الموتى الـ20 الألبان، طلبوا الخلاص بالدم. أحد المنازل، Hadži-Kosta، أعطى 17 ضحية.[14] في الليل، وعندما أوقف التعب والجوع المذبحة، أحصى العسكريين الموتى.

الميراث

أسفرت الهزيمة العثمانية لصربيا إلى جانب الظروف الجيوسياسية الجديدة بعد عام 1878 التي عارضها القوميون الألبان عن مواقف معادية للمسيحيين من بينهم أيدت في نهاية المطاف ما يعرف اليوم باسم "التطهير العرقي" الذي جعل جزءا من سكان صرب كوسوفو يغادرون.[21]

قبل حروب البلقان (1912-1913)، صرح زعيم مجتمع صرب كوسوفو جانجييجي بوبوفيتش أن حروب 1876-1878 "تضاعف" كراهية الأتراك والألبان ثلاثة أضعاف، وخاصة حرب اللاجئين من سانجاك نيي تجاه الصرب من خلال ارتكابها أعمال عنف ضدهم.[10]

المراجع

- Frantz, Eva Anne (2009). "Violence and its Impact on Loyalty and Identity Formation in Late Ottoman Kosovo: Muslims and Christians in a Period of Reform and Transformation". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 29 (4): 460–461. doi:10.1080/13602000903411366.

- Müller, Dietmar (2009). "Orientalism and Nation: Jews and Muslims as Alterity in Southeastern Europe in the Age of Nation-States, 1878–1941". East Central Europe. 36 (1): 63–99. doi:10.1163/187633009x411485. "For Serbia the war of 1878, where the Serbians fought side by side with Russian and Romanian troops against the Ottoman Empire, and the Berlin Congress were of central importance, as in the Romanian case. The beginning of a new quality of the Serbian-Albanian history of conflict was marked by the expulsion of Albanian Muslims from Niš Sandžak which was part and parcel of the fighting (Clewing 2000 : 45ff.; Jagodić 1998 ; Pllana 1985). Driving out the Albanians from the annexed territory, now called "New Serbia," was a result of collaboration between regular troops and guerrilla forces, and it was done in a manner which can be characterized as ethnic cleansing, since the victims were not only the combatants, but also virtually any civilian regardless of their attitude towards the Serbians (Müller 2005b). The majority of the refugees settled in neighboring Kosovo where they shed their bitter feelings on the local Serbs and ousted some of them from merchant positions, thereby enlarging the area of Serbian-Albanian conflict and intensifying it."

- Stefanović, Djordje (2005). "Seeing the Albanians through Serbian eyes: The Inventors of the Tradition of Intolerance and their Critics, 1804–1939". European History Quarterly. 35 (3): 469. مؤرشف من الأصل في 09 سبتمبر 2015. "In 1878, following a series of Christian uprisings against the Ottoman Empire, the Russo-Turkish War, and the Berlin Congress, Serbia gained complete independence, as well as new territories in the Toplica and Kosanica regions adjacent to Kosovo. These two regions had a sizable Albanian population which the Serbian government decided to deport."; p.470. "The ‘cleansing’ of Toplica and Kosanica would have long-term negative effects on Serbian-Albanian relations. The Albanians expelled from these regions moved over the new border to Kosovo, where the Ottoman authorities forced the Serb population out of the border region and settled the refugees there. Janjićije Popović, a Kosovo Serb community leader in the period prior to the Balkan Wars, noted that after the 1876–8 wars, the hatred of the Turks and Albanians towards the Serbs ‘tripled’. A number of Albanian refugees from Toplica region, radicalized by their experience, engaged in retaliatory violence against the Serbian minority in Kosovo... The 1878 cleansing was a turning point because it was the first gross and large-scale injustice committed by Serbian forces against the Albanians. From that point onward, both ethnic groups had recent experiences of massive victimization that could be used to justify ‘revenge’ attacks. Furthermore, Muslim Albanians had every reason to resist the incorporation into the Serbian state."

- Lampe, 2000, p. 55. نسخة محفوظة 6 فبراير 2020 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Pllana, Emin (1985). "Les raisons de la manière de l'exode des refugies albanais du territoire du sandjak de Nish a Kosove (1878–1878) [The reasons for the manner of the exodus of Albanian refugees from the territory of the Sanjak of Niš to Kosovo (1878–1878)] ". Studia Albanica. 1: 189–190.

- Rizaj, Skënder (1981). "Nënte Dokumente angleze mbi Lidhjen Shqiptare të Prizrenit (1878–1880) [Nine English documents about the League of Prizren (1878–1880)]". Gjurmine Albanologjike (Seria e Shkencave Historike). 10: 198.

- Şimşir, Bilal N, (1968). Rumeli’den Türk göçleri. Emigrations turques des Balkans [Turkish emigrations from the Balkans]. Vol I. Belgeler-Documents. p. 737.

- Bataković, Dušan (1992). The Kosovo Chronicles. Plato. مؤرشف من الأصل في 28 أبريل 2019.

- Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Kosovo. Scarecrow Press. صفحة XXXII. .

- Stefanović, Djordje (2005). "Seeing the Albanians through Serbian eyes: The Inventors of the Tradition of Intolerance and their Critics, 1804–1939". European History Quarterly. 35 (3): 469. "In 1878, following a series of Christian uprisings against the Ottoman Empire, the Russo-Turkish War, and the Berlin Congress, Serbia gained complete independence, as well as new territories in the Toplica and Kosanica regions adjacent to Kosovo. These two regions had a sizable Albanian population which the Serbian government decided to deport."; p.470. "The ‘cleansing’ of Toplica and Kosanica would have long-term negative effects on Serbian-Albanian relations. The Albanians expelled from these regions moved over the new border to Kosovo, where the Ottoman authorities forced the Serb population out of the border region and settled the refugees there. Janjićije Popović, a Kosovo Serb community leader in the period prior to the Balkan Wars, noted that after the 1876–8 wars, the hatred of the Turks and Albanians towards the Serbs ‘tripled’. A number of Albanian refugees from Toplica region, radicalized by their experience, engaged in retaliatory violence against the Serbian minority in Kosovo... The 1878 cleansing was a turning point because it was the first gross and large-scale injustice committed by Serbian forces against the Albanians. From that point onward, both ethnic groups had recent experiences of massive victimization that could be used to justify ‘revenge’ attacks. Furthermore, Muslim Albanians had every reason to resist the incorporation into the Serbian state."

- Lampe 2000.

- Frantz, Eva Anne (2009). "Violence and its Impact on Loyalty and Identity Formation in Late Ottoman Kosovo: Muslims and Christians in a Period of Reform and Transformation". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 29 (4): 460–461. doi:10.1080/13602000903411366.

- Müller, Dietmar (2009). "Orientalism and Nation: Jews and Muslims as Alterity in Southeastern Europe in the Age of Nation-States, 1878–1941". East Central Europe. 36 (1): 63–99. doi:10.1163/187633009x411485. "For Serbia the war of 1878, where the Serbians fought side by side with Russian and Romanian troops against the Ottoman Empire, and the Berlin Congress were of central importance, as in the Romanian case. The beginning of a new quality of the Serbian-Albanian history of conflict was marked by the expulsion of Albanian Muslims from Niš Sandžak which was part and parcel of the fighting (Clewing 2000 : 45ff.; Jagodić 1998 ; Pllana 1985). Driving out the Albanians from the annexed territory, now called "New Serbia," was a result of collaboration between regular troops and guerrilla forces, and it was done in a manner which can be characterized as ethnic cleansing, since the victims were not only the combatants, but also virtually any civilian regardless of their attitude towards the Serbians (Müller 2005b). The majority of the refugees settled in neighboring Kosovo where they shed their bitter feelings on the local Serbs and ousted some of them from merchant positions, thereby enlarging the area of Serbian-Albanian conflict and intensifying it."

- Krakov 1990

- Institut za savremenu istoriju 2007

- Krakov 1990، صفحة 12

- Popović 1900.

- Krakov 1990.

- Društvo sv. Save 1928.

- Društvo sv. Save 1930.

- Little 2007.

مصادر

- Krakov, Stanislav (1990) [1930]. Plamen četništva (باللغة الصربية). Belgrade: Hipnos. (in Serbian)

- Institut za savremenu istoriju (2007). Gerila na Balkanu (باللغة الصربية). Tokyo: Institute for Disarmament and Peace Studies. (in Serbian)

- Popović, Zarija R. (1900). Pred Kosovom: beleške iz doba 1874-1878 godine. Drž. štamp. Kralj. Srbije. صفحات 86–87.

Панађуриште беше центар арнаутских напада. Дођоше пет Арнаута пред врата Јованове куће и стадоше лупати.

- Milan Budisavljević; Paja Adamov Marković; Dragutin J. Ilić (1899). Brankovo kolo za zabavu, pouku i književnost. 5.

Али догађај 26. јануара 1878. године остаће крвавим словима записан на лнетоии- ма историје града Приштине.

- Društvo sv. Save (1928). Brastvo. 22. Društvo sv. Save. صفحة 58.

Али је напад поглавито био управљен на Панађуриште, а у Панађуришту на кућу Јована Ђаковца. Јован је по зањимању пушкар. Његово српско одушев- љење било је појачано утицајем приштевачког учитеља Кова- чевића, коме је Јован често одлазио. И кад би Јован са својим шеснаестогодишњим сином ишао јутром у дућан, или се ве- чером враћао из дућана, били су вазда наоружани револверима и мартинкама. Турци би на овако наоружане кауре попреко гледали, ...

- Društvo sv. Save (1930). Brastvo. 24–26. Društvo sv. Save.

После неколико дана је у Приштини настала сеча Срба од Арнаута Малесораца којих је био пун град. Нарочито је био напад у махали Панађуришту на кућу непокорног Јована Ђаковца пушкара. Јован се јуначки борио, док му није кућа упаљена те му загрожена опасносг да се у диму угуши или да у пламену изгори. Заменивши своје главе десетороструко главама арнаутским, најзад су јуначки пали Јован, жена му и шурак.

- Lampe, John R. (28 March 2000). Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country. Cambridge University Press. .

- Little, David (2007). Peacemakers in Action: Profiles of Religion in Conflict Resolution. Cambridge University Press. .

- Михаило Воjводић (1978). Србија 1878: документи. Српска књижевна задруга.

- Vladimir Stojančević (1998). Srpski narod u Staroj Srbiji u Velikoj istočnoj krizi 1876-1878. Službeni list SRJ.

- Bor. M. Karapandžić (1986). Srpsko Kosovo i Metohija: zločini Arnauta nad srpskim narodom. sn.n.