وجدت الدراسات العلمية أن العديد من المناطق الدماغية تظهر نشاط متغير في المرضى الذين يعانون من الاكتئاب، وهذا ما شجع دعاة النظريات المختلفة التي تسعى إلى تحديد أصل بيوكيميائي للمرض، على عكس النظريات التي تأكد على الأسباب النفسية. وقد اقترحت عدة نظريات حول السبب البيولوجي للاكتئاب على مر السنين، بما في ذلك النظريات التي تدور حول المواد الكيميائية الناقلة واللدونة العصبية والالتهاب ونظم يوماوي.

الأسباب الجينية

كان من الصعب تحديد العوامل الوراثية التي تؤدي إلى الاكتئاب. في عام 2003 نشرت مجلة ساينس نشرت دراسة[1] وجدت أن التفاعلات الجينية والبيئة المحيطة قد تفسر لماذا الإجهاد ومتطلبات الحياة قد تكون مؤشراً لنوبات الاكتئاب في بعض الأفراد، ولكن ليس في غيرها، وهذا يتوقف على الاختلاف في مستقبلات السيروتونين (5 HTTLPR).[2] بعد فترة وجيزة، تم تكرار النتائج من قبل مجموعة كينيث كيندلر، مما رفع الآمال في مجتمع علم الوراثة النفسية.[3] ومع ذلك فإن اثنان من أكبر الدراسات [4][5] كانت نتائجهم بالسلب.[6] اثنان من الدراسات في 2009 كانت نتائجهم أيضاً سلبية، واحدة منهم كانت تحوي 14 بحثاُ.[7][8][9]

تم افتراض أن تعدد أشكال عامل التغذية العصبية المستمد من الدماغ قد يكون له تأثير وراثي، ولكن النتائج كانت غير كافية.[10] وتشير الدراسات أيضا إلى وجود ارتباط بانخفاض إنتاج عامل التغذية العصبية المستمد من الدماغ مع السلوك الانتحاري.[11] ومع ذلك فإن نتائج دراسات التفاعلات بين الجينات والبيئة قد وجدت أن النمتذج الحالية من عامل التغذية العصبية المستمد من الدماغ هي نماذج مبسطة للغاية [12][12][13]

فشلت أكبر الدراسات على نطاق الجينوم حتى الآن في تحديد المتغيرات ذات الأهمية الجينية في أكثر من 9000 حالة.[14]

في الآونة الأخيرة، حددت دراسة الوراثة بشكل إيجابي اثنين من المتغيرات هما الارتباط على نطاق الجينوم مع الاضطراب الاكتئابي.[15] حيث حددت هذه الدراسة، التي أجريت في نساء مدينة هان الصينية، نوعين مختلفين من المستقبلات SIRT1 وLHPP .[16]

وقد أسفرت محاولات إيجاد علاقة بين أشكال تعدد النورأدرينالين والاكتئاب عن نتائج سلبية.[17]

وحددت إحدى المراجعات العديد من الجينات التي تمت دراستها بشكل متكرر. أسفرت الجينات 5-HTT SLC6A4 و5-HTR2A عن نتائج غير متناسقة، إلا أنها قد تتنبأ بنتائج العلاج. وقد وجد أن تعدد الأشكال في جينات إنزيم تربتوفان هيدروكسيلاس تكون مرتبطة بالسلوك الانتحاري.[18][19]

النظم اليوماوي

قد يكون الاكتئاب مرتبطاً بآليات الدماغ نفسها التي تتحكم في دورات النوم واليقظة. وقد يكون الاكتئاب مرتبطا بشذوذ في نظم يوماوي,[20] أو الساعة البيولوجية. على سبيل المثال، نوم حركة العين السريعة(REM) - وهي المرحلة التي يحدث فيها الحلم - قد تكون سريعة الحدوث ومكثفة في مرضي الاكتئاب. نوم حركة العين السريعة تعتمد على انخفاض مستوي السيروتونين في جذع الدماغ,[21] وتضعف من قبل مركبات، مثل مضادات الاكتئاب التي تزيد من قوة السيروتونين في جذع الدماغ.[21] وعموما، فإن نظام السيروتونين يكون أقل نشاطا أثناء النوم وأكثر نشاطا أثناء اليقظة.كثرة الاستيقاظ نتيجة اضطراب النوم[20] ينشط الخلايا العصبية السيروتونينية، مما يؤدي إلى عمليات مماثلة للتأثير العلاجي لمضادات الاكتئاب، مثل مثبطات امتصاص السيروتونين الانتقائية (SSRIs). مرضي الاكتئاب تظهر لديهم تقلبات في المزاج بعد ليلة من الحرمان من النوم.[21]

تشير الأبحاث المتعلقة بآثار العلاج بالضوء في حالات الاضطراب العاطفي الموسمي إلى أن الحرمان الخفيف من النوم مرتبط بانخفاض النشاط في النظام السيروتوني، وإلى تشوهات في دورة النوم، لا سيما الأرق. التعرض للضوء يستهدف أيضا نظام السيروتونين، موفراً المزيد من الأدلة للدور الهام الذي يلعب هذا النظام في آلية الاكتئاب.[22] الحرمان من النوم والعلاج بالضوء كلاهما يستهدف نفس النظام العصبي في الدماغ مثل الأدوية المضادة للاكتئاب، وتستخدم الآن سريريا لعلاج الاكتئاب.[23] يتم استخدام العلاج بالضوء، والحرمان من النوم معاً لمقاطعة الاكتئاب العميق بسرعة في المرضى في المستشفى.[22]

وقد وجد أن زيادة ونقص فترة النوم تلعب دوراً هاماً في آلية الاكتئاب.[24] المرضى الذين يعانون من الاكتئاب الكبير يظهرون أحيانا تغيرا يومية وموسمية في شدة الأعراض، حتى في الاكتئاب غير الموسمي. ارتبط تحسن المزاج النهاري مع نشاط الشبكات العصبية الظهرية. كما لوحظ ارتفاع متوسط درجة الحرارة الأساسية. واقترحت إحدى الفرضيات أن الاكتئاب كان نتيجة للانتقال من مرحلة إلي مرحلة ومن طور إلي طور.[25]

يرتبط التعرض للضوء أثناء النهار بانخفاض نشاط ناقل السيروتونين، والذي قد يكمن وراء موسمية الاكتئاب.[26]

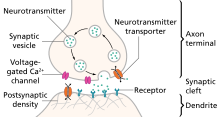

النواقل العصبية أحادية الأمين

هي ناقلات عصبية تشمل السيروتونين، والدوبامين، ونورإبينفرين، وأدرينالين.[27][28] العديد من العقاقير مضادات الاكتئاب تزيد مستويات الناقل العصبي أحادي الأمين، السيروتونين، ولكنها قد تعزز أيضا مستويات اثنين من الناقلات العصبية الأخرى، النورادرينالين والدوبامين. وأدت مراقبة هذه الفعالية إلى "فرضية الناقل العصبي أحادي الأمين، الاكتئاب"، التي تفترض أن عجز بعض الناقلات العصبية هي المسؤولة عن ظهور أعراض الاكتئاب: "قد يكون نورإبينفرين مرتبطا باليقظة والطاقة فضلا عن القلق والانتباه، والاهتمام بالحياة؛ نقص السيروتونين مرتبط بالقلق، والهواجس، والإكراه، والدوبامين مرتبط بالاهتمام والدافع والمتعة والمكافأة، فضلا عن الاهتمام بالحياة ". يوصي أنصار هذه الفرضية اختيار مضادات الاكتئاب المناسبة ذات الآلية التي تؤثر على أبرز الأعراض.[29][30] واقترح آخرون أيضا العلاقة بين الناقلات العصبية أحادية الأمين ونمط ظاهري مثل السيروتونين في النوم والانتحار، والتعب، واللامبالاة، والخلل المعرفي، والدوبامين في فقدان الدافع والأعراض النفسية الحركية.[2][31][32][33]

وقد تم الإبلاغ عن العثور على دلالة على انخفاض نشاط الأدرينالين في الاكتئاب. وتشمل النتائج انخفاض نشاط إنزيم تيروزين هيدروكسيلاز، وزيادة كثافة مستقبلات الأدرينالين ألفا 2، وانخفاض كثافة المستقبلات ألفا 1 .[36] وعلاوة على ذلك، فإن إفراز النورابينفرين في نماذج الفئران أدي إلي قلة حساسية المستقبلات، مما يلعب دوراً كبيراً في الاكتئاب.[37]

طريقة واحدة استخدمت لدراسة دور النقلات العصبية أحادية الأمين وهي استنزاف هذه الناقلات العصبية. نفاذ التريبتوفان (مصدر تكوين السيروتونين)، والتيروزين والفينيل ألانين (مصدر تكوين الدوبامين) يؤدي إلى انخفاض المزاج في أولئك الذين لديهم استعداد للاكتئاب، ولكن ليس الأشخاص الأصحاء.[38][39][40][41][42][43]

القيود

منذ التسعينات، كشفت الأبحاث عن قيود متعددة على فرضية الناقلات أحادية الأمين، وقد تم انتقاد قصورها في المجتمع النفسي.[44][45][46] فشلت التحقيقات المكثفة في العثور على أدلة مقنعة على وجود خلل وظيفي أساسي في نظام أحادي الأمين في المرضى الذين يعانون من اضطراب اكتئابي.[47][48][49][50][51]

التفاعلات العاطفية

تظهر دراسات المعالجة العاطفية لدى مرضى الاكتئاب الكبير التحيزات المختلفة مثل الميل إلى تقييم الوجوه السعيدة بشكل أكثر سلبية.[52][53] وقد أظهر التصوير العصبي الوظيفي فرط النشاط في مناطق الدماغ المختلفة ردا على المحفزات العاطفية السلبية، ونقص النشاط استجابة لمؤثرات إيجابية. وقد ظهر أيضاً انخفاض النشاط في قشرة الفص الجبهي ردا على المحفزات السلبية.[54][55][56]

وهناك فرضية مقترحة للتحيز العاطفي السلبي تأتي من النتائج التحليلية الوصفية لدراسات التصوير العصبي الوظيفي.[57][58][59]

مناطق الدماغ

البحوث على أدمغة المرضى المكتئبين عادة ما تظهر أنماط مضطربة من التفاعل بين أجزاء متعددة من الدماغ. العديد من مناطق الدماغ متورطة في الدراسات التي تسعى إلى فهم أكثر تفهما لبيولوجيا الاكتئاب:

نواة راف

المصدر الوحيد ل السيروتونين في الدماغ هو نواة راف، وهي مجموعة من الخلايا العصبية الصغيرة في الجزء العلوي من جذع الدماغ، وتقع مباشرة في منتصف خط الدماغ..[60]

تلفيف حزامي

وقد أظهرت الدراسات الحديثة أن التلفيف الحزامي (منطقة برودمان 25) غنية للغاية بناقلات السيروتونين، وتعتبر المتحكمة في شبكة واسعة تشمل مناطق مثل تحت المهاد وجذع الدماغ، مما يؤثر على التغيرات في الشهية والنوم.[61][62]

البطين

وقد وجدت دراسات متعددة أدلة على توسيع البطين في الأشخاص الذين يعانون من الاكتئاب، ولا سيما توسيع البطين الثالث.[63][64][65] ويفسر هذا بأنه فقدان الأنسجة العصبية في مناطق الدماغ المجاورة للبطين المتوسع.[66][67][68]

قشرة أمام جبهية

وقد لوحظ نقص النشاط في قشرة أمام جبهية في أولئك الذين يعانون من الاكتئاب.[69] وتشارك القشرة الأمام جبهية في المعالجة العاطفية والتنظيم، وقد يكون الخلل في هذه العملية متورطا في مسببات الاكتئاب.[70][71][72]

اللوزة الدماغية

لوزة دماغية هي منطقة تشارك في المعالجة العاطفية وقد تبين أنه يكون هناك فرط في نشاطها في أولئك الذين يعانون من اضطراب الاكتئاب الكبير.[62] حيث كانت اللوزة الدماغية في الأشخاص الذين يعانون من الاكتئاب أصغر من تلك في الأشخاص الذين تم علاجهم، إلا أن البيانات المجمعة لا تظهر أي فرق بين الأشخاص المصابين بالاكتئاب والأصحاء.[73][74][75]

قرن آمون (الحصين)

وقد لوحظ ضمور في قرن آمون ( الحصين ) خلال الاكتئاب.[76][77][78][79]

الإجهاد يمكن أن يسبب الاكتئاب والأعراض التي تشبه الاكتئاب من خلال التأثير علي الخلايا العصبية في الحصين.[80][81][82][83][84][85]

الالتهاب والإجهاد التأكسدي

وقد وجدت دراسات مختلفة أن الالتهابات قد تلعب دورا في الاكتئاب.[86][87][88] ظهرت النظريات الأولى عندما لوحظ أن العلاج بالإنترفيرون يسبب الاكتئاب في عدد كبير من المرضى.[89] أظهرت بعض التحليلات أن مستويات السيتوكين في المرضى الذين يعانون من الاكتئاب تتزايد وخصوصاً إنترلوكين 1، وإنترلوكين 6 ولكن ليس إنترلوكين 10.[90][91][92] وقد افترضت مصادر مختلفة من الالتهاب في مرض الاكتئاب تشمل الصدمة، ومشاكل النوم، والنظام الغذائي، والتدخين والبدانة.[93][94][95][96][97]

الشبكة التنفيذية المركزية

تتكون الوظائف التنفيذية أو الشبكة التنفيذية من المنطقة الجبهية الجدارية، بما في ذلك القشرة الأمامية الجبهية الظهرانية والجانبية.[98][99] وتشارك هذه الشبكة بشكل حاسم في الوظائف الإدراكية عالية المستوى مثل الحفاظ على المعلومات واستخدامها في الذاكرة العاملة وحل المشكلات واتخاذ القرارات.[100][101][102][103][104] أوجه القصور في هذه الشبكة تكون شائعة في معظم الاضطرابات النفسية والعصبية الرئيسية، بما في ذلك الاكتئاب.[105][106] لأن هذه الشبكة هي أمر بالغ الأهمية لأنشطة الحياة اليومية، حيث أن أولئك الذين يعانون من الاكتئاب يمكن أن تظهر لديهم ضعف في الأنشطة الأساسية مثل اتخاذ القرارات.[107]

شبكة الوضع الافتراضي

تتضمن شبكة الوضع الافتراضي محاور في قشرة الفص الجبهي، مع مناطق بارزة أخرى من الشبكة في الفص الصدغي.[100][108] شبكة الوضع الافتراضي عادة ما تكون نشطة أثناء التفكير والمناقشة المواقف الاجتماعية. في المقابل، فإنه العلوم المعرفية الإدراكية فإن الشبكة الافتراضية غالبا ما يتم تعطيلها.[109][110][111][112][113]

مقالات ذات صلة

المراجع

- Nierenberg, AA (2009). "The long tale of the short arm of the promoter region for the gene that encodes the serotonin uptake protein" ( كتاب إلكتروني PDF ). CNS spectrums. 14 (9): 462–3. doi:10.1017/s1092852900023506. PMID 19890228. مؤرشف من الأصل ( كتاب إلكتروني PDF ) في 4 مارس 2012.

- Caspi, Avshalom; Sugden, Karen; Moffitt, Terrie E.; Taylor, Alan; Craig, Ian W.; Harrington, HonaLee; McClay, Joseph; Mill, Jonathan; Martin, Judy; Braithwaite, Antony; Poulton, Richie (July 2003). "Influence of Life Stress on Depression: Moderation by a Polymorphism in the 5-HTT Gene". Science. 301 (5631): 386–89. Bibcode:2003Sci...301..386C. doi:10.1126/science.1083968. PMID 12869766. مؤرشف من الأصل في 5 أكتوبر 2015.

- Kendler, K.; Kuhn, J.; Vittum, J.; Prescott, C.; Riley, B. (2005). "The interaction of stressful life events and a serotonin transporter polymorphism in the prediction of episodes of major depression: a replication". Archives of General Psychiatry. 62 (5): 529–535. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.529. PMID 15867106. ضع ملخصا – New Hot Paper Comments (6 September 2006).

- Gillespie, N. A.; Whitfield, J. B.; Williams, B.; Heath, A. C.; Martin, N. G. (2005). "The relationship between stressful life events, the serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) genotype and major depression". Psychological Medicine. 35 (1): 101–111. doi:10.1017/S0033291704002727. PMID 15842033.

- Surtees, P.; Wainwright, N.; Willis-Owen, S.; Luben, R.; Day, N.; Flint, J. (2006). "Social adversity, the serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism and major depressive disorder". Biological Psychiatry. 59 (3): 224–229. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.014. PMID 16154545.

- Uher, R.; McGuffin, P. (2008). "The moderation by the serotonin transporter gene of environmental adversity in the aetiology of mental illness: review and methodological analysis". Molecular Psychiatry. 13 (2): 131–146. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4002067. PMID 17700575.

- Risch, N.; Herrell, R.; Lehner, T.; Liang, K.; Eaves, L.; Hoh, J.; Griem, A.; Kovacs, M.; Ott, J.; Merikangas, K. R. (2009). "Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis". Journal of the American Medical Association. 301 (23): 2462–2471. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.878. PMC . PMID 19531786.

- Munafo, M.; Durrant, C.; Lewis, G.; Flint, J. (2009). "Gene × Environment Interactions at the Serotonin Transporter Locus". Biological Psychiatry. 65 (3): 211–219. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.009. PMID 18691701.

- Uher, R.; McGuffin, P. (2010). "The moderation by the serotonin transporter gene of environmental adversity in the etiology of depression: 2009 update". Molecular Psychiatry. 15 (1): 18–22. doi:10.1038/mp.2009.123. PMID 20029411.

- Levinson, D. (2006). "The genetics of depression: a review". Biological Psychiatry. 60 (2): 84–92. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.024. PMID 16300747.

- Dwivedi Y (2009). "Brain-derived neurotrophic factor: role in depression and suicide". Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 5: 433–49. doi:10.2147/NDT.S5700. PMC . PMID 19721723.

- Krishnan, V.; Nestler, E. (2008). "The molecular neurobiology of depression". Nature. 455 (7215): 894–902. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..894K. doi:10.1038/nature07455. PMC . PMID 18923511.

- Pezawas, L.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Goldman, A. L.; Verchinski, B. A.; Chen, G.; Kolachana, B. S.; Egan, M. F.; Mattay, V. S.; Hariri, A. R.; Weinberger, D. R. (2008). "Evidence of biologic epistasis between BDNF and SLC6A4 and implications for depression". Molecular Psychiatry. 13 (7): 709–716. doi:10.1038/mp.2008.32. PMID 18347599.

- Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric GWAS Consortium; Ripke, S; Wray, N. R.; Lewis, C. M.; Hamilton, S. P.; Weissman, M. M.; Breen, G; Byrne, E. M.; Blackwood, D. H.; Boomsma, D. I.; Cichon, S; Heath, A. C.; Holsboer, F; Lucae, S; Madden, P. A.; Martin, N. G.; McGuffin, P; Muglia, P; Noethen, M. M.; Penninx, B. P.; Pergadia, M. L.; Potash, J. B.; Rietschel, M; Lin, D; Müller-Myhsok, B; Shi, J; Steinberg, S; Grabe, H. J.; Lichtenstein, P; et al. (2013). "A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressive disorder". Molecular Psychiatry. 18 (4): 497–511. doi:10.1038/mp.2012.21. PMC . PMID 22472876.

- Converge Consortium; Bigdeli, Tim B.; Kretzschmar, Warren; Li, Yihan; Liang, Jieqin; Song, Li; Hu, Jingchu; Li, Qibin; Jin, Wei; Hu, Zhenfei; Wang, Guangbiao; Wang, Linmao; Qian, Puyi; Liu, Yuan; Jiang, Tao; Lu, Yao; Zhang, Xiuqing; Yin, Ye; Li, Yingrui; Xu, Xun; Gao, Jingfang; Reimers, Mark; Webb, Todd; Riley, Brien; Bacanu, Silviu; Peterson, Roseann E.; Chen, Yiping; Zhong, Hui; Liu, Zhengrong; et al. (2015). "Sparse whole-genome sequencing identifies two loci for major depressive disorder". Nature. 523 (7562): 588–91. doi:10.1038/nature14659. PMC . PMID 26176920.

- Smoller, Jordan W (2015). "The Genetics of Stress-Related Disorders: PTSD, Depression, and Anxiety Disorders". Neuropsychopharmacology. Springer Nature. 41 (1): 297–319. doi:10.1038/npp.2015.266. مؤرشف من الأصل في 11 مايو 202024 مارس 2017.

- Zhao, Xiaofeng; Huang, Yinglin; Ma, Hui; Jin, Qiu; Wang, Yuan; Zhu, Gang (15 August 2013). "Association between major depressive disorder and the norepinephrine transporter polymorphisms T-182C and G1287A: a meta-analysis". Journal of Affective Disorders. 150 (1): 23–28. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.03.016. ISSN 1573-2517. PMID 23648227.

- Lohoff, Falk W. (6 December 2016). "Overview of the Genetics of Major Depressive Disorder". Current psychiatry reports. 12 (6): 539–546. doi:10.1007/s11920-010-0150-6. ISSN 1523-3812. PMC . PMID 20848240.

- López-León, S.; Janssens, A. C. J. W.; González-Zuloeta Ladd, A. M.; Del-Favero, J.; Claes, S. J.; Oostra, B. A.; van Duijn, C. M. (1 August 2008). "Meta-analyses of genetic studies on major depressive disorder". Molecular Psychiatry. 13 (8): 772–785. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4002088. ISSN 1476-5578. PMID 17938638.

- Carlson, Neil R. (2013). Physiology of behavior (الطبعة 11th). Boston: Pearson. صفحات 578–582. . OCLC 769818904.

- Adrien J.. Neurobiological bases for the relation between sleep and depression. Sleep Medicine Review. 2003;6(5):341–51. معرف الوثيقة الرقمي:10.1053/smrv.2001.0200. PMID 12531125.

- Terman M. Evolving applications of light therapy. Sleep Medicine Review. 2007;11(6):497–507. معرف الوثيقة الرقمي:10.1016/j.smrv.2007.06.003. PMID 17964200.

- Benedetti F, Barbini B, Colombo C, Smeraldi E. Chronotherapeutics in a psychiatric ward. Sleep Medicine Review. 2007;11(6):509–22. معرف الوثيقة الرقمي:10.1016/j.smrv.2007.06.004. PMID 17689120.

- Zhai, Long; Zhang, Hua; Zhang, Dongfeng (1 September 2015). "SLEEP DURATION AND DEPRESSION AMONG ADULTS: A META-ANALYSIS OF PROSPECTIVE STUDIES". Depression and Anxiety. 32 (9): 664–670. doi:10.1002/da.22386. ISSN 1520-6394. PMID 26047492.

- Germain, Anne; Kupfer, David J. (6 December 2016). "CIRCADIAN RHYTHM DISTURBANCES IN DEPRESSION". Human psychopharmacology. 23 (7): 571–585. doi:10.1002/hup.964. ISSN 0885-6222. PMC . PMID 18680211.

- Savitz, Jonathan B.; Drevets, Wayne C. (1 April 2013). "Neuroreceptor imaging in depression". Neurobiology of Disease. 52: 49–65. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2012.06.001. ISSN 1095-953X. PMID 22691454.

- Carlson, Neil R. (2005). Foundations of Physiological Psychology (الطبعة 6th). Boston: Pearson A and B. صفحة 108. . OCLC 60880502.

- Lammel, S.; Tye, K. M.; Warden, M. R. (1 January 2014). "Progress in understanding mood disorders: optogenetic dissection of neural circuits". Genes, Brain and Behavior (باللغة الإنجليزية). 13 (1): 38–51. doi:10.1111/gbb.12049. ISSN 1601-183X. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2 سبتمبر 2017.

- Nutt DJ (2008). "Relationship of neurotransmitters to the symptoms of major depressive disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 69 Suppl E1: 4–7. PMID 18494537.

- Kunugi, Hiroshi; Hori, Hiroaki; Ogawa, Shintaro (1 October 2015). "Biochemical markers subtyping major depressive disorder". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 69 (10): 597–608. doi:10.1111/pcn.12299. ISSN 1440-1819. PMID 25825158.

- Marchand; Valentina; Jensen. "Neurobiology of Mood disorders". Hospital physician: 17–26.

- "Asymmetry and mood, emergent properties of serotonin regulation: A proposed mechanism of action of lithium". Archives of General Psychiatry. 36 (8): 909–16. 1979. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780080083019. PMID 454111.

- Dunlop, Boadie W.; Nemeroff, Charles B. (1 April 2007). "The Role of Dopamine in the Pathophysiology of Depression". Archives of General Psychiatry. 64 (3): 327–37. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.327. ISSN 0003-990X. PMID 17339521. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2 مايو 2020.

- Carlson, N. (2013). Physiology of behavior. (11 ed., pp. 575–576). United States of America: Pearson.

- Willner, Paul (1 December 1983). "Dopamine and depression: A review of recent evidence. I. Empirical studies". Brain Research Reviews. 6 (3): 211–224. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(83)90005-X. مؤرشف من الأصل في 3 يوليو 2019.

- HASLER, GREGOR (4 December 2016). "PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF DEPRESSION: DO WE HAVE ANY SOLID EVIDENCEOF INTEREST TO CLINICIANS?". World Psychiatry. 9 (3): 155–161. ISSN 1723-8617. PMC . PMID 20975857.

- Delgado PL, Moreno FA (2000). "Role of norepinephrine in depression". J Clin Psychiatry. 61 Suppl 1: 5–12. PMID 10703757.

- Ruhe, HG; Mason, NS; Schene, AH (2007). "Mood is indirectly related to serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine levels in humans: a meta-analysis of monoamine depletion studies". Molecular Psychiatry. 12: 331–359. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001949. PMID 17389902.

- "Elevated monoamine oxidase a levels in the brain: An explanation for the monoamine imbalance of major depression". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (11): 1209–16. November 2006. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1209. PMID 17088501. مؤرشف من الأصل في 26 أبريل 2012.

- "Association of monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) polymorphisms and clinical subgroups of major depressive disorders in the Han Chinese population". World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. Informa Healthcare. 10 (4 Pt 2): 544–51. 2007-12-19. doi:10.1080/15622970701816506. PMID 19224413. مؤرشف من الأصل في 11 مايو 202020 سبتمبر 2008.

- "Association study of a monoamine oxidase a gene promoter polymorphism with major depressive disorder and antidepressant response". Neuropsychopharmacology. 30 (9): 1719–23. September 2005. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300785. PMID 15956990.

- "Interactions of child maltreatment and serotonin transporter and monoamine oxidase A polymorphisms: depressive symptomatology among adolescents from low socioeconomic status backgrounds". Dev. Psychopathol. 19 (4): 1161–80. 2007. doi:10.1017/S0954579407000600. PMID 17931441.

- Castrén, E (2005). "Is mood chemistry?". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 6 (3): 241–46. doi:10.1038/nrn1629. PMID 15738959.

- Hirschfeld RM (2000). "History and evolution of the monoamine hypothesis of depression". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 61 Suppl 6: 4–6. PMID 10775017.

- al.], editors, Kenneth L. Davis ... [et (2002). Neuropsychopharmacology : the fifth generation of progress : an official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (الطبعة 5th). Philadelphia, Pa.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. صفحات 1139–1163. .

- Savitz, Jonathan; Drevets, Wayne (2013). "Neuroreceptor imaging in depression". Neurobiology of Disease. 52: 49–65. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2012.06.001. PMID 22691454.

- Jacobsen, Jacob P. R.; Medvedev, Ivan O.; Caron, Marc G. (5 September 2012). "The 5-HT deficiency theory of depression: perspectives from a naturalistic 5-HT deficiency model, the tryptophan hydroxylase 2Arg439His knockin mouse". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 367 (1601): 2444–2459. doi:10.1098/rstb.2012.0109. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC . PMID 22826344.

- "Role of norepinephrine in depression". J Clin Psychiatry. 61 Suppl 1: 5–12. 2000. PMID 10703757.

- Delgado PL (2000). "Depression: the case for a monoamine deficiency". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 61 Suppl 6: 7–11. PMID 10775018.

- Andrews, Paul W.; Bharwani, Aadil; Lee, Kyuwon R.; Fox, Molly; Thomson, J. Anderson (1 April 2015). "Is serotonin an upper or a downer? The evolution of the serotonergic system and its role in depression and the antidepressant response". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 51: 164–188. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.01.018. ISSN 1873-7528. PMID 25625874.

- Lacasse, Jeffrey R.; Leo, Jonathan (8 November 2005). "Serotonin and Depression: A Disconnect between the Advertisements and the Scientific Literature". PLoS Medicine. 2 (12): e392. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020392. PMC . PMID 16268734. مؤرشف من الأصل في 07 مارس 2020.

- Bourke, Cecilia; Douglas, Katie; Porter, Richard (1 August 2010). "Processing of facial emotion expression in major depression: a review". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 44 (8): 681–696. doi:10.3109/00048674.2010.496359. ISSN 1440-1614. PMID 20636189.

- Sternat T, Katzman MA (1 January 2016). "Neurobiology of hedonic tone: the relationship between treatment-resistant depression, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and substance abuse". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment (باللغة الإنجليزية). 12: 2149–64. doi:10.2147/NDT.S111818. PMC . PMID 27601909.

- Groenewold, Nynke A.; Opmeer, Esther M.; de Jonge, Peter; Aleman, André; Costafreda, Sergi G. (1 February 2013). "Emotional valence modulates brain functional abnormalities in depression: evidence from a meta-analysis of fMRI studies". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 37 (2): 152–163. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.11.015. ISSN 1873-7528. PMID 23206667.

- Dalili, M. N.; Penton-Voak, I. S.; Harmer, C. J.; Munafò, M. R. (7 December 2016). "Meta-analysis of emotion recognition deficits in major depressive disorder". Psychological Medicine. 45 (6): 1135–1144. doi:10.1017/S0033291714002591. ISSN 0033-2917. PMC . PMID 25395075.

- Harmer, C. J.; Goodwin, G. M.; Cowen, P. J. (31 July 2009). "Why do antidepressants take so long to work? A cognitive neuropsychological model of antidepressant drug action". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 195 (2): 102–108. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.051193.

- Hamilton, J. Paul; Etkin, Amit; Furman, Daniella J.; Lemus, Maria G.; Johnson, Rebecca F.; Gotlib, Ian H. (1 July 2012). "Functional neuroimaging of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and new integration of base line activation and neural response data". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 169 (7): 693–703. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11071105. ISSN 1535-7228. PMID 22535198.

- Mayberg, Helen (1 August 1997). "Limbic-cortical dysregulation: a proposed model of depression". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 9 (3): 471–481. doi:10.1176/jnp.9.3.471. ISSN 0895-0172. مؤرشف من الأصل في 9 يناير 2020.

- Graham, Julia; Salimi-Khorshidi, Gholamreza; Hagan, Cindy; Walsh, Nicholas; Goodyer, Ian; Lennox, Belinda; Suckling, John (1 November 2013). "Meta-analytic evidence for neuroimaging models of depression: State or trait?". Journal of Affective Disorders. 151 (2): 423–431. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.002. مؤرشف من الأصل في 3 يوليو 2019.

- Salomon, RM; Cowan, RL (November 2013). "Oscillatory serotonin function in depression". Synapse (New York, N.Y.). 67 (11): 801–20. PMC . PMID 23592367.

- Carlson, Neil R. (2012). Physiology of Behavior Books a La Carte Edition (الطبعة 11th ed.). Boston: Pearson College Div. .

- Miller, Chris H.; Hamilton, J. Paul; Sacchet, Matthew D.; Gotlib, Ian H. (1 October 2015). "Meta-analysis of Functional Neuroimaging of Major Depressive Disorder in Youth". JAMA psychiatry. 72 (10): 1045–1053. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1376. ISSN 2168-6238. PMID 26332700.

- Hendrie, C.A.; Pickles, A.R. (2009). "Depression as an evolutionary adaptation: Implications for the development of preclinical models". Medical Hypotheses. 72 (3): 342–347. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2008.09.053. PMID 19153014. مؤرشف من الأصل في 13 ديسمبر 201925 سبتمبر 2013.

- Hendrie, C.A.; Pickles, A.R. (2010). "Depression as an evolutionary adaptation: Anatomical organisation around the third ventricle". Medical Hypotheses. 74 (4): 735–740. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2009.10.026. PMID 19931308. مؤرشف من الأصل في 7 سبتمبر 201825 سبتمبر 2013.

- Sheline, Yvette (August 2003). "Neuroimaging studies of mood disorder effects on the brain". Biological Psychiatry. 54 (3): 338–352. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00347-0. PMID 12893109. مؤرشف من الأصل في 9 يناير 202025 سبتمبر 2013.

- Manji, Husseini K.; Quiroz, Jorge A.; Sporn, Jonathan; Payne, Jennifer L.; Denicoff, Kirk; Gray, Neil A.; Zarate Jr., Carlos A.; Charney, Dennis S. (April 2003). "Enhancing neuronal plasticity and cellular resilience to develop novel, improved therapeutics for difficult-to-treat depression". Biological Psychiatry. 53: 707–742. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00117-3. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2 مايو 202025 سبتمبر 2013.

- Miller, A. H.; Maletic, V.; Raison, C. L. (2009). "Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression". Biological Psychiatry. 65 (9): 732–741. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029. PMC . PMID 19150053.

- Raison, C. L.; Capuron, L.; Miller, A. H. (2006). "Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression". Trends in Immunology. 27 (1): 24–31. doi:10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006. PMC . PMID 16316783.

- Wessa, Michèle; Lois, Giannis (30 November 2016). "Brain Functional Effects of Psychopharmacological Treatment in Major Depression: A Focus on Neural Circuitry of Affective Processing". Current Neuropharmacology. 13 (4): 466–479. doi:10.2174/1570159X13666150416224801. ISSN 1570-159X. PMC . PMID 26412066.

- Outhred, Tim; Hawkshead, Brittany E.; Wager, Tor D.; Das, Pritha; Malhi, Gin S.; Kemp, Andrew H. (1 September 2013). "Acute neural effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors on emotion processing: Implications for differential treatment efficacy". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 37 (8): 1786–1800. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.07.010. ISSN 1873-7528. PMID 23886514.

- Hamilton, J. Paul; Etkin, Amit; Furman, Daniella J.; Lemus, Maria G.; Johnson, Rebecca F.; Gotlib, Ian H. "Functional Neuroimaging of Major Depressive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis and New Integration of Baseline Activation and Neural Response Data". American Journal of Psychiatry. 169 (7): 693–703. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11071105. PMID 22535198. مؤرشف من الأصل في 9 يناير 2020.

- Fitzgerald, Paul B.; Laird, Angela R.; Maller, Jerome; Daskalakis, Zafiris J. (20 May 2010). "A Meta-Analytic Study of Changes in Brain Activation in Depression". Human brain mapping. 29 (6): 683–695. doi:10.1002/hbm.20426. ISSN 1065-9471. PMC . PMID 17598168.

- Hamilton, J. Paul; Siemer, Matthias; Gotlib, Ian H. (8 Sept 2009). "Amygdala volume in Major Depressive Disorder: A meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies". Molecular Psychiatry. 13 (11): 993–1000. doi:10.1038/mp.2008.57. ISSN 1359-4184. PMC . PMID 18504424.

- Palmer, Susan M.; Crewther, Sheila G.; Carey, Leeanne M. (14 January 2015). "A Meta-Analysis of Changes in Brain Activity in Clinical Depression". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.01045. ISSN 1662-5161. PMC . PMID 25642179.

- Fitzgerald, Paul B.; Laird, Angela R.; Maller, Jerome; Daskalakis, Zafiris J. (5 December 2016). "A Meta-Analytic Study of Changes in Brain Activation in Depression". Human brain mapping. 29 (6): 683–695. doi:10.1002/hbm.20426. ISSN 1065-9471. PMC . PMID 17598168.

- Cole, James; Costafreda, Sergi G.; McGuffin, Peter; Fu, Cynthia H. Y. (1 November 2011). "Hippocampal atrophy in first episode depression: a meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies". Journal of Affective Disorders. 134 (1–3): 483–487. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.057. ISSN 1573-2517. PMID 21745692.

- Videbech, Poul; Ravnkilde, Barbara (1 November 2004). "Hippocampal volume and depression: a meta-analysis of MRI studies". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 161 (11): 1957–1966. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1957. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 15514393.

- Arana, G. W.; Baldessarini, R. J.; Ornsteen, M. (1 December 1985). "The dexamethasone suppression test for diagnosis and prognosis in psychiatry. Commentary and review". Archives of General Psychiatry. 42 (12): 1193–1204. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790350067012. ISSN 0003-990X. PMID 3000317.

- Varghese, Femina P.; Brown, E. Sherwood (1 January 2001). "The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis in Major Depressive Disorder: A Brief Primer for Primary Care Physicians". Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 3 (4): 151–155. doi:10.4088/pcc.v03n0401. ISSN 1523-5998. PMC . PMID 15014598.

- Mahar, I; Bambico, FR; Mechawar, N; Nobrega, JN (January 2014). "Stress, serotonin, and hippocampal neurogenesis in relation to depression and antidepressant effects". Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 38: 173–92. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.11.009. PMID 24300695.

- Willner, P; Scheel-Krüger, J; Belzung, C (December 2013). "The neurobiology of depression and antidepressant action". Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 37 (10 Pt 1): 2331–71. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.12.007. PMID 23261405.

- "The HPA axis in major depression: classical theories and new developments". Trends Neurosci. 31 (9): :464–468. September 2008. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2008.06.006. PMID 18675469.

- Belvederi Murri, Martino; Pariante, Carmine; Mondelli, Valeria; Masotti, Mattia; Atti, Anna Rita; Mellacqua, Zefiro; Antonioli, Marco; Ghio, Lucio; Menchetti, Marco; Zanetidou, Stamatula; Innamorati, Marco; Amore, Mario (1 March 2014). "HPA axis and aging in depression: systematic review and meta-analysis". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 41: 46–62. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.12.004. ISSN 1873-3360. PMID 24495607.

- Juruena, Mario F. (1 September 2014). "Early-life stress and HPA axis trigger recurrent adulthood depression". Epilepsy & Behavior: E&B. 38: 148–159. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.10.020. ISSN 1525-5069. PMID 24269030.

- Heim, Christine; Newport, D. Jeffrey; Mletzko, Tanja; Miller, Andrew H.; Nemeroff, Charles B. (1 August 2008). "The link between childhood trauma and depression: Insights from HPA axis studies in humans". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 33 (6): 693–710. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.008. ISSN 0306-4530. PMID 18602762. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2 مايو 2020.

- Krishnadas, Rajeev; Cavanagh, Jonathan (1 May 2012). "Depression: an inflammatory illness?". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 83 (5): 495–502. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2011-301779. ISSN 1468-330X. PMID 22423117.

- Patel, Amisha (1 September 2013). "Review: the role of inflammation in depression". Psychiatria Danubina. 25 Suppl 2: S216–223. ISSN 0353-5053. PMID 23995180.

- Dowlati, Yekta; Herrmann, Nathan; Swardfager, Walter; Liu, Helena; Sham, Lauren; Reim, Elyse K.; Lanctôt, Krista L. (1 March 2010). "A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression". Biological Psychiatry. 67 (5): 446–457. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033. ISSN 1873-2402. PMID 20015486.

- Dantzer, Robert; O’Connor, Jason C.; Freund, Gregory G.; Johnson, Rodney W.; Kelley, Keith W. (3 December 2016). "From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 9 (1): 46–56. doi:10.1038/nrn2297. ISSN 1471-003X. PMC . PMID 18073775.

- Hiles, Sarah A.; Baker, Amanda L.; de Malmanche, Theo; Attia, John (1 October 2012). "A meta-analysis of differences in IL-6 and IL-10 between people with and without depression: exploring the causes of heterogeneity". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 26 (7): 1180–1188. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2012.06.001. ISSN 1090-2139. PMID 22687336.

- Howren, M. Bryant; Lamkin, Donald M.; Suls, Jerry (1 February 2009). "Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: a meta-analysis". Psychosomatic Medicine. 71 (2): 171–186. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907c1b. ISSN 1534-7796. PMID 19188531.

- Maes, Michael (29 April 2011). "Depression is an inflammatory disease, but cell-mediated immune activation is the key component of depression". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 35 (3): 664–675. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.06.014. ISSN 1878-4216. PMID 20599581.

- Berk, Michael; Williams, Lana J; Jacka, Felice N; O’Neil, Adrienne; Pasco, Julie A; Moylan, Steven; Allen, Nicholas B; Stuart, Amanda L; Hayley, Amie C; Byrne, Michelle L; Maes, Michael (12 September 2013). "So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from?". BMC Medicine. 11: 200. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-200. ISSN 1741-7015. PMC . PMID 24228900.

- Leonard, Brian; Maes, Michael (1 February 2012). "Mechanistic explanations how cell-mediated immune activation, inflammation and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways and their sequels and concomitants play a role in the pathophysiology of unipolar depression". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 36 (2): 764–785. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.12.005. ISSN 1873-7528. PMID 22197082.

- Raedler, Thomas J. (1 November 2011). "Inflammatory mechanisms in major depressive disorder". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 24 (6): 519–525. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32834b9db6. ISSN 1473-6578. PMID 21897249.

- Black, Catherine N.; Bot, Mariska; Scheffer, Peter G.; Cuijpers, Pim; Penninx, Brenda W. J. H. (1 January 2015). "Is depression associated with increased oxidative stress? A systematic review and meta-analysis". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 51: 164–175. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.09.025. ISSN 1873-3360. PMID 25462890.

- Schutte, Nicola S.; Malouff, John M. (1 April 2015). "The association between depression and leukocyte telomere length: a meta-analysis". Depression and Anxiety. 32 (4): 229–238. doi:10.1002/da.22351. ISSN 1520-6394. PMID 25709105.

- Seeley, W.W; et al. (February 2007). "Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control". The Journal of Neuroscience. 27.

- Habas, C; et al. (1 July 2009). "Distinct cerebellar contributions to intrinsic connectivity networks". The Journal of Neuroscience. 29.

- Menon, Vinod (October 2011). "Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 15 (10): 483–506. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2011.08.003. PMID 21908230.

- Petrides, M (2005). "Lateral prefrontal cortex: architecture and functional organization". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 360 (1456): 781–795. doi:10.1098/rstb.2005.1631.

- Koechlin, E; Summerfield, C (2007). "An information theoretical approach to prefrontal executive function". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 11 (6): 229–235. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2007.04.005. PMID 17475536.

- Miller, E.K.; Cohen, J.D. (2001). "An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 24: 167–202. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. PMID 11283309.

- Muller, N.G.; Knight, R.T. (2006). "The functional neuroanatomy of working memory: contributions of human brain lesion studies". Neuroscience. 139 (1): 51–58. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.09.018. PMID 16352402.

- Woodward, N.D.; et al. (2011). "Functional resting-state networks are differentially affected in schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Research. 130 (1–3): 86–93. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.010. PMC . PMID 21458238.

- Menon, Vinod; et al. (2001). "Functional neuroanatomy of auditory working memory in schizophrenia: relation to positive and negative symptoms". NeuroImage. 13 (3): 433–446. doi:10.1006/nimg.2000.0699. PMID 11170809.

- Levin, R.L.; et al. (2007). "Cognitive deficits in depression and functional specificity of regional brain activity". Cognitive Therapy and Research. 31 (2): 211–233. doi:10.1007/s10608-007-9128-z.

- Feinstein, J.S.; et al. (September 2006). "Anterior insula reactivity during certain decisions is associated with neuroticism". Social Cognition and Affective Neuroscience. 1 (2): 136–142. doi:10.1093/scan/nsl016.

- Qin, P; Northoff, G (2011). "How is our self related to midline regions and the default mode network?". NeuroImage. 57 (3): 1221–1233. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.028. PMID 21609772.

- Raichle, M.E.; et al. (2001). "A default mode of brain function". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (2): 676–682. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. PMC . PMID 11209064.

- Cooney, R.E.; et al. (2010). "Neural correlates of rumination in depression". Cognitive Affective and Behavioral Neuroscience. 10 (4): 470–478. doi:10.3758/cabn.10.4.470.

- Broyd, S.J.; et al. (2009). "Default mode brain dysfunction in mental disorders: a systematic review". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 33 (3): 279–296. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.002. PMID 18824195.

- Hamani, C; et al. (15 February 2011). "The subcallosal cingulate gyrus in the context of major depression". Biological Psychiatry. 69 (4): 301–8. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.034. PMID 21145043.

للمزيد من القراءة

- Szafran, K; Faron-Górecka, A; Kolasa, M; Kuśmider, M; Solich, J; Zurawek, D; Dziedzicka-Wasylewska, M (2013). "Potential role of G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) heterodimerization in neuropsychiatric disorders: a focus on depression" ( كتاب إلكتروني PDF ). Pharmacol Rep. 65 (6): 1498–505. doi:10.1016/s1734-1140(13)71510-x. PMID 24552997. مؤرشف من الأصل ( كتاب إلكتروني PDF ) في 10 يناير 2017.

- Naumenko, VS; Popova, NK; Lacivita, E; Leopoldo, M; Ponimaskin, EG (July 2014). "Interplay between serotonin 5-HT1A and 5-HT7 receptors in depressive disorders". CNS Neurosci Ther. 20 (7): 582–90. doi:10.1111/cns.12247. PMID 24935787. مؤرشف من الأصل في 17 يونيو 2016.